Ayer mi papá cumplió once días en el hospital.

Once días y finalmente salimos.

Entró porque tuvo unas crisis convulsivas. Feas. Fuertes. La primera le pasó sin que yo lo viera. La segunda me tocó, pero no la quise ver. Me salí del cuarto.

Las otras me tocaron completas. Tuve que verlas. Tuve que quedarme.

Pensé que mi papá no regresaba. No que se muriera. Que no regresaba su cabeza.

Nos hablaron de derrame cerebral, nos hablaron de embolia, no fue ninguna de esas. Esperamos la primera noche en terapia intensiva, en esos sillones verdes que tantos malos recuerdos me traen.

Al siguiente día no había habla.

Luego hablo pero se quedó trabado. No en la memoria. Trabado en su mente. En un delirio. No podía salir de ahí.

Fue impactante. Fue muy pinche doloroso.

En once días de hospital lo sientes todo.

Sientes miedo.

Sientes tristeza.

Sientes pérdida.

Sientes frustración.

Sientes también la mediocridad de los que te rodean.

La vocación de algunos doctores. La indiferencia de otros.

La entrega de algunas enfermeras. El desdén de otras.

Ves a muchos estudiantes de medicina, los jóvenes, los que apenas están saliendo. Les avientan casos que no saben manejar. No les dan la información completa o de plano no se tratan de informar.

Nadie sabe nada. Nadie se hace cargo.

Todos se tiran la pelota.

Te preguntan 100 veces que medicamentos toma el paciente, los apuntan en papeles efímeros, no hay una carpeta, no sirve de nada contestar tantas preguntas.

Nadie vuelve a saber nada de su historial. Le dan medicamentos que lo tumban, le quitan medicamentos que le causan síndrome de abstinencia, le tiemblan las manos, todos te dicen que ese temblor ya existía. Tú sabes que no es cierto. Volteas a ver a tu padre intentando agarrar torpemente su periódico y los quieres matar.

Te das cuenta de que el sistema no funciona.

Te enojas. Te agotas. Te rompe.

En el hospital no hay tiempo

Las horas pasan lentas.

Las luces de hospital son algo verdadero. Son horribles. Son blancas. Mal colocadas. Te hacen ver mal. Hacen ver muy mal al paciente. Hacen que se vea mal el presente y el futuro.

Es una iluminación que causa tristeza. Una iluminación para ver la verdad tal cual es.

En el hospital no hay filtros. No hay manera de no escuchar.

A Juliana le tocó escuchar a una intern de neurología en el pasillo, diciendo que como familia estábamos mal, que no queríamos aceptar el estado de mi papá. Que él había llegado así.

Pero mi papá no llegó así. Mi papá llegó con la cabeza bien. Con su memoria. Lo que tenía eran 85 años y deterioro cognitivo de la edad. Pero no delirios.

No confundir a su hermana con su madre.

No perderse completamente.

Lo vieron ya dañado y asumieron que siempre fue así.

Cada nuevo doctor al que veías había que explicarle todo otra vez. Lo que dijo el anterior. Lo que ya sabíamos nosotros. Era desesperante.

La neuróloga (perdón por la definición), una perra condescendiente.

Dicen que es muy buena. Y probablemente lo es. Pero le falta humanidad. Trata mal. A mí me vale madres, pero a él también lo trataba así. Como si no valiera la pena hablarle. Como si fuese un trámite explicarle. Como si no hubiera nada que rescatar.

Eso también duele.

Otros doctores, al contrario, fueron maravillosos.

El cardiólogo. El de nutrición. El otorrino. El urólogo.

Tratamos con ocho doctores.

Ocho.

Ocho reportes que tuvimos que juntar para que nos dejaran irnos.

Ocho firmas, ocho argumentos, ocho cartas para el seguro, ocho recetas médicas.

Y el seguro. Ese que mis papás han pagado toda su vida. Una póliza altísima. Y cuando toca que respondan, te cuestionan todo. Te hacen demostrarlo todo. Te hacen mendigar lo que ya pagaste.

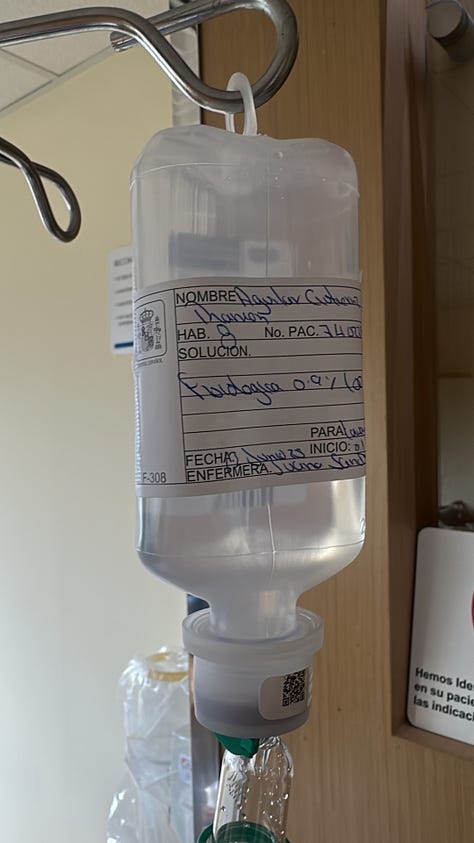

Mi papá no puede comer por la boca, paso 5 días con solo el suero. Gracias a Dios por la sonda.

Nosotros comíamos en la cafetería. Había mejor internet, podías trabajar media hora. Pero los doctores pasaban cuando pasaban, y alguien tenía que estar ahí para escuchar. En ese hospital no hay quien te ayude, todo el tiempo debes cuidar tu a tu paciente.

El hospital Español huele a miedo. El elevador siempre va atascado. Sientes que nadie cabe, pero todos se meten.

El Hospital Español está triste. Olvidado. Tan viejo como los pacientes que atienden en terapia media.

Muy doloroso mirar hacia los cuartos y ver a la gente. Muy mayor. Muy enferma. Sola. Sin visitas.

Yo pensaba, ¿qué pasa con esa gente?, ¿Qué pasa con quienes no tienen hijos que vivan en México?, ¿Qué pasa con la gente mayor cuando ya no le queda nadie que lo cuide?

También pensé en mí, porque soy una egoísta, y sentía una culpa desmedida y me salía a llorar al pasillo.

Pensaba, ¿y dónde queda mi vida?. Llevo once días sin ir al súper. Once días sin pisar mi casa más que para mal dormir. Once días de llegar tan cansada que tenía que pedir a los hijos que no me hablaran.

Once días sin pararme en la oficina. Sin atender mi trabajo. Sin comer bien. Dejando cosas vitales en pausa.

Cuando tienes que cuidar a un padre mayor, se detiene todo.

Y no hay reemplazo. No hay quien entre en tu lugar.

Todo lo que te han dicho sobre cuidar a los padres que envejecen, es absolutamente verdad. Yo solo lo medio sabía.

En once días se te viene encima tu infancia.

Tus heridas.

Tus reclamos.

Tus aprendizajes.

Todo lo que hizo bien tu papá.

Todo lo que hizo mal.

En once días se te derrumba la fantasía de que hay un sistema que te va a cuidar.

Y descubres que no.

En once días descubres que solo somos mi hermano y yo. En turnos que no son humanos.

Que gracias a Dios por Maribel, que dormía con él y le tocaba la peor parte.

Ayer salimos del hospital. Pero no regresamos a la casa que conocíamos en Maimonides. Regresamos a una casa que ahora es otra cosa.

Cama nueva, barandales, enfermeras por turnos.

Un papá que no recuerda por qué tiene una sonda. Cuando de hecho tiene dos.

Una mamá que ha estado confundida, a quien también tuvimos que descuidar por estar con mi padre. Una mamá que hace preguntas y se frustra por olvidar. Sufre.

Y así serán las cosas ahora.

No es fácil.

Nada fácil.

Pero es mejor que estar once días en el hospital.

Y por ahora, es suficiente.

IN ENGLISH:

Yesterday marked eleven days since my dad was admitted to the hospital.

Eleven days—and we finally got out.

He was admitted after having a series of seizures. Bad ones. Intense. The first one happened without me seeing it. I was there for the second, but I chose not to see it. I walked out of the room.

The others—I witnessed in full. I had to see them. I had to stay.

I thought my dad wasn’t coming back. Not that he’d die. But that his mind wouldn’t come back.

They mentioned a stroke, an embolism—but it was neither. We spent the first night in the ICU, in those green chairs that bring back so many bad memories.

The next day, there was no speech.

Then he spoke, but he got stuck. Not his memory. Stuck in his mind. In a delirium. He couldn’t get out of it.

It was shocking. And fucking painful.

In eleven days at the hospital, you feel everything.

You feel fear.

You feel sadness.

You feel loss.

You feel frustration.

You also feel the mediocrity of those around you.

The vocation of some doctors. The indifference of others.

The dedication of certain nurses. The disdain of others.

You see lots of med students—the young ones, the ones just starting out. They get thrown into cases they don’t know how to handle. No one gives them all the info, or they simply don’t take the time to find out.

No one knows anything. No one takes responsibility.

Everyone just passes the buck.

You’re asked a hundred times what medications the patient takes. They write them down on flimsy pieces of paper. No folder. No system. Answering those questions does nothing.

No one ever knows his history. They give him meds that knock him out. They take away others that cause withdrawal symptoms. His hands tremble, and they all say, “Oh, that tremor was already there.” You know that’s not true. You look at your dad clumsily trying to grab his newspaper, and you want to kill them.

You realize the system doesn’t work.

You get angry. You get drained. It breaks you.

There is no sense of time in the hospital.

The hours crawl.

Hospital lighting is a real thing. It’s awful. It’s white. Harsh. Misplaced. It makes everyone look bad. It makes the patient look terrible. It makes the present and future look terrible.

It’s the kind of lighting that breeds sadness. Lighting that forces you to see the truth exactly as it is.

There are no filters in a hospital. No way to unhear things.

Juliana overheard a neurology intern in the hallway saying our family was in denial, that we didn’t want to accept my dad’s condition. That he had arrived that way.

But my dad didn’t arrive that way. He came in with his mind intact. With his memory. What he had were 85 years and age-related cognitive decline. But not delusions.

Not confusing his sister for his mother.

Not completely losing himself.

They saw someone already damaged and assumed he had always been that way.

With every new doctor, you had to explain everything again. What the last one had said. What we already knew. It was maddening.

The neurologist (pardon the term), was a condescending bitch.

They say she’s brilliant. And maybe she is. But she lacks humanity. She treats people poorly. I couldn’t care less how she treats me, but she treated him that way too. Like he wasn’t worth speaking to. Like explaining things to him was just another box to tick. Like there was nothing left to save.

And that hurts too.

Other doctors, in contrast, were wonderful.

The cardiologist. The nutritionist. The ENT. The urologist.

We dealt with eight doctors.

Eight.

Eight reports we had to collect to be allowed to leave.

Eight signatures, eight explanations, eight letters for the insurance, eight prescriptions.

And the insurance—the one my parents have paid all their lives. A hefty policy. And when it’s time for them to show up, they question everything. Make you prove everything. Make you beg for what you’ve already paid for.

My dad can’t eat by mouth. He went five days with just an IV. Thank God for the feeding tube.

We ate in the cafeteria. The internet was better, you could work for half an hour. But doctors came when they came, and someone had to be there to listen. In that hospital, there’s no one to help you. You have to be there to care for your patient at all times.

Hospital Español smells like fear. The elevator is always packed. You feel like no one else could possibly fit—but everyone squeezes in.

Hospital Español is sad. Forgotten. As old as the patients they treat in intermediate care.

It’s painful to look into the rooms and see people. Very old. Very sick. Alone. No visitors.

I kept thinking: what happens to them? What happens to those without kids in Mexico? What happens to the elderly when there’s no one left to care for them?

I also thought of myself—because I’m selfish—and I felt a huge wave of guilt and would slip into the hallway to cry.

I’d think: where is my life in all this? It’s been eleven days without going to the supermarket. Eleven days of barely sleeping at home. Eleven days of coming home so tired I’d have to ask the kids not to talk to me.

Eleven days of not setting foot in my office. Of not tending to work. Of not eating properly. Of putting vital things on pause.

When you’re taking care of an aging parent, everything else stops.

And there’s no substitute. No one can take your place.

Everything they say about caring for aging parents is absolutely true. I only kind of knew it.

In eleven days, your childhood comes flooding back.

Your wounds.

Your grievances.

Your life lessons.

Everything your dad did right.

Everything he did wrong.

In eleven days, the fantasy that the system will take care of you comes crashing down.

And you discover it won’t.

In eleven days, you realize it’s just my brother and me. Taking shifts that aren’t humanly possible.

And thank God for Maribel, who slept with him and got the worst of it.

Yesterday we left the hospital. But we didn’t return to the house we once knew on Maimonides. We came back to a house that is now something else.

A new bed, guardrails, nurses working in shifts.

A father who doesn’t remember why he has a feeding tube. When in fact, he has two.

A mother who’s been confused—whom we also had to neglect while caring for him. A mother who asks questions and gets frustrated when she forgets. She suffers.

And this is how things will be now.

It’s not easy.

Not at all.

But it’s better than being in the hospital for eleven days.

And for now, it’s enough.

Me recordó al año más difícil de mi vida con mi mamá, cuando perdió la salud de un instante a otro. Nadie te prepara para lo duro que es. Un abrazo solidario.

Te abrazo